Can't we just translate between simplified and traditional Chinese characters?

Last week, I discussed the meaning of simplified vs traditional Chinese characters. I had discussed the differences in them, and pointed out that in most sentences, there are only a few characters that are different between the character sets.

So, it would seem that the obvious question is why we can’t then just simply translate between the two character sets.

Ironically, it is the simplification process itself that has made this difficult.

It is quite easy to have a computer translate traditional Chinese characters to simplified ones. The problem is the reverse.

This is well-described in the academic paper Key Problems in Conversion from Simplified to Traditional Chinese Characters by Xiaodong Shi, Yidong Chen, and Xiuping Huang.

The first reason that this is a problem is that in some cases, more than one traditional character was mapped to the same simplified character. Let’s see an example:

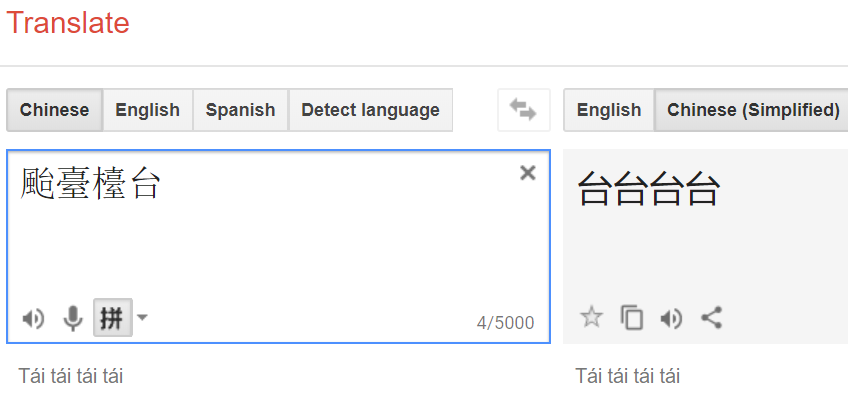

Each of these four characters:

was translated to this character:

as you can see in the main image above this post.

So when you need to translate back the other way, which character do you translate it to?

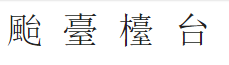

The answer is that you need context, and that’s where over time, computers will get better and better than humans at doing this, but not quite yet. Here’s another example:

This one is easy for the system as it knows that Táifēng (a typhoon) is a specific thing and knows which character to use.

A second part of the challenge though is also shown in the example above. Note that the name Táifēng is somewhat similar to the English word typhoon. That’s no accident. It’s what’s called a 通假 (or Tōngjiǎ) which is called a loan word, based on phonetics, not on the meaning of the characters directly.

Loan words are very difficult to translate back to traditional characters because the only context is the loan word itself. These groups of characters often have little meaning by themselves.

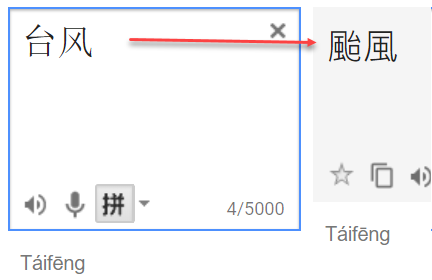

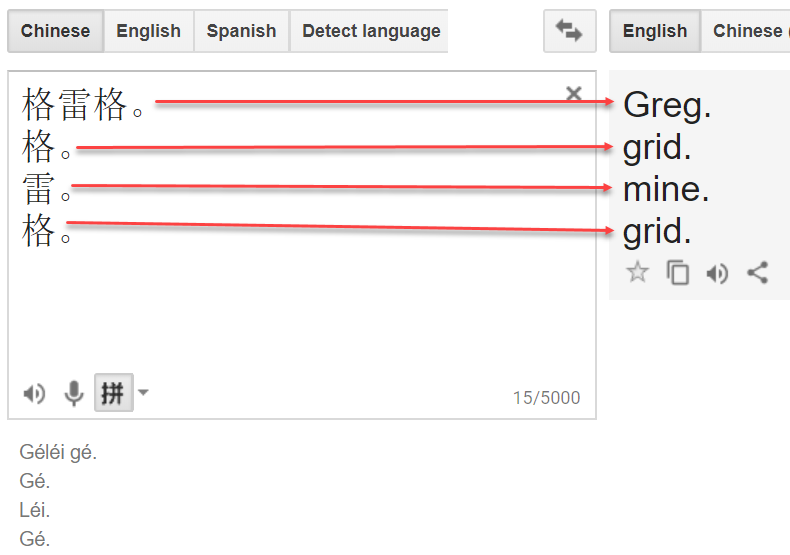

For example, my name Greg is often written like this:

But now look at the meaning of the individual characters:

Note that “grid, mine, grid” isn’t particularly meaningful on its own. It’s only when the entire name is present, that Google Translate has any clue about what it means, and then it’s only an “educated” guess.

As an interesting side note, it’s also why a lot of westerners spend ages trying to find a suitable Chinese name, much the same way that I have Chinese friends who have chosen western names.

The most notable of these is probably Mark Rowswell (大山 or Dàshān) whose name means Big Mountain. That’s more exciting than mine. If you’d like to see him doing standup comedy in China, just browse for either Mark Rowswell or Dashan in YouTube.

2018-08-04